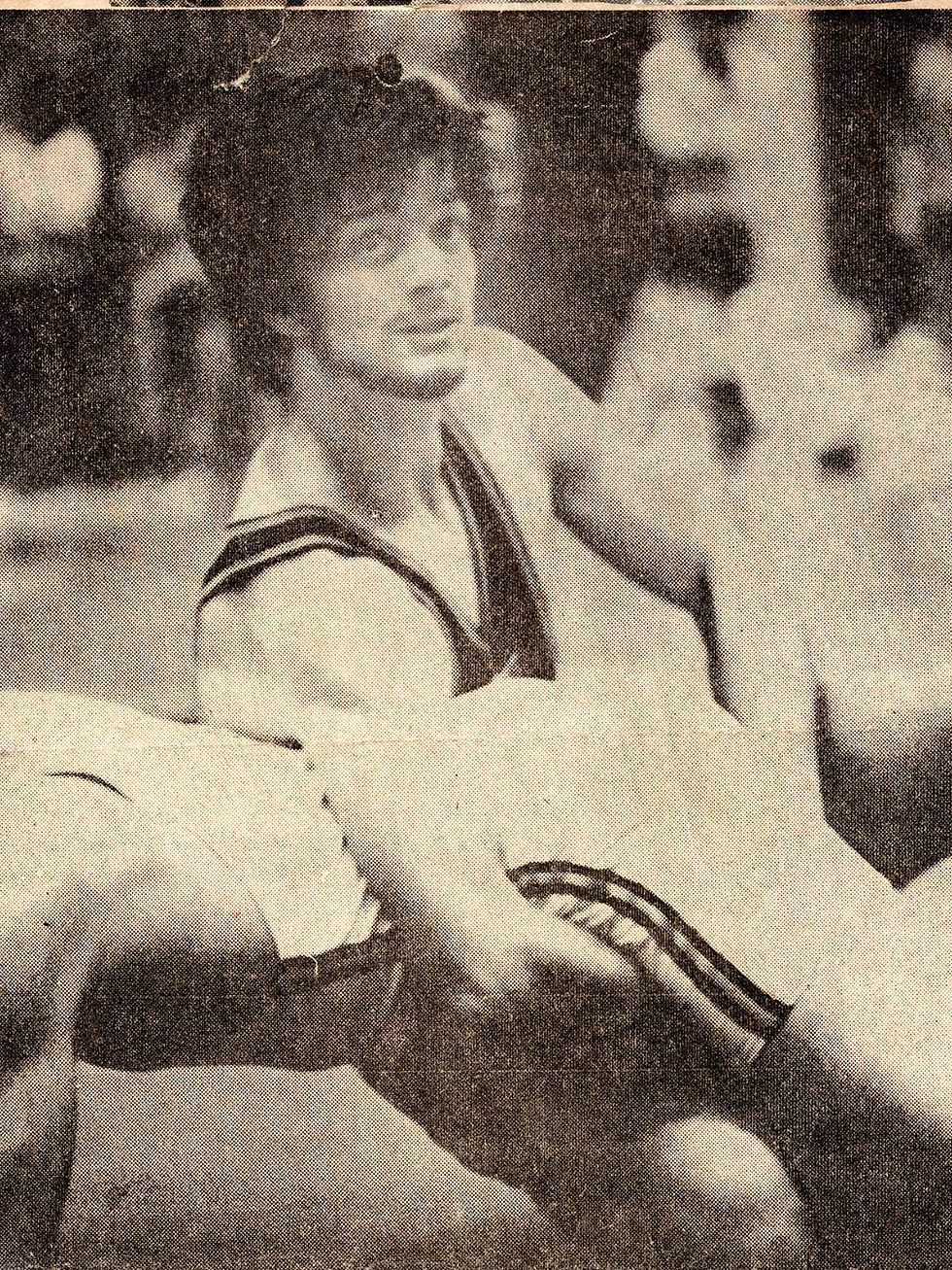

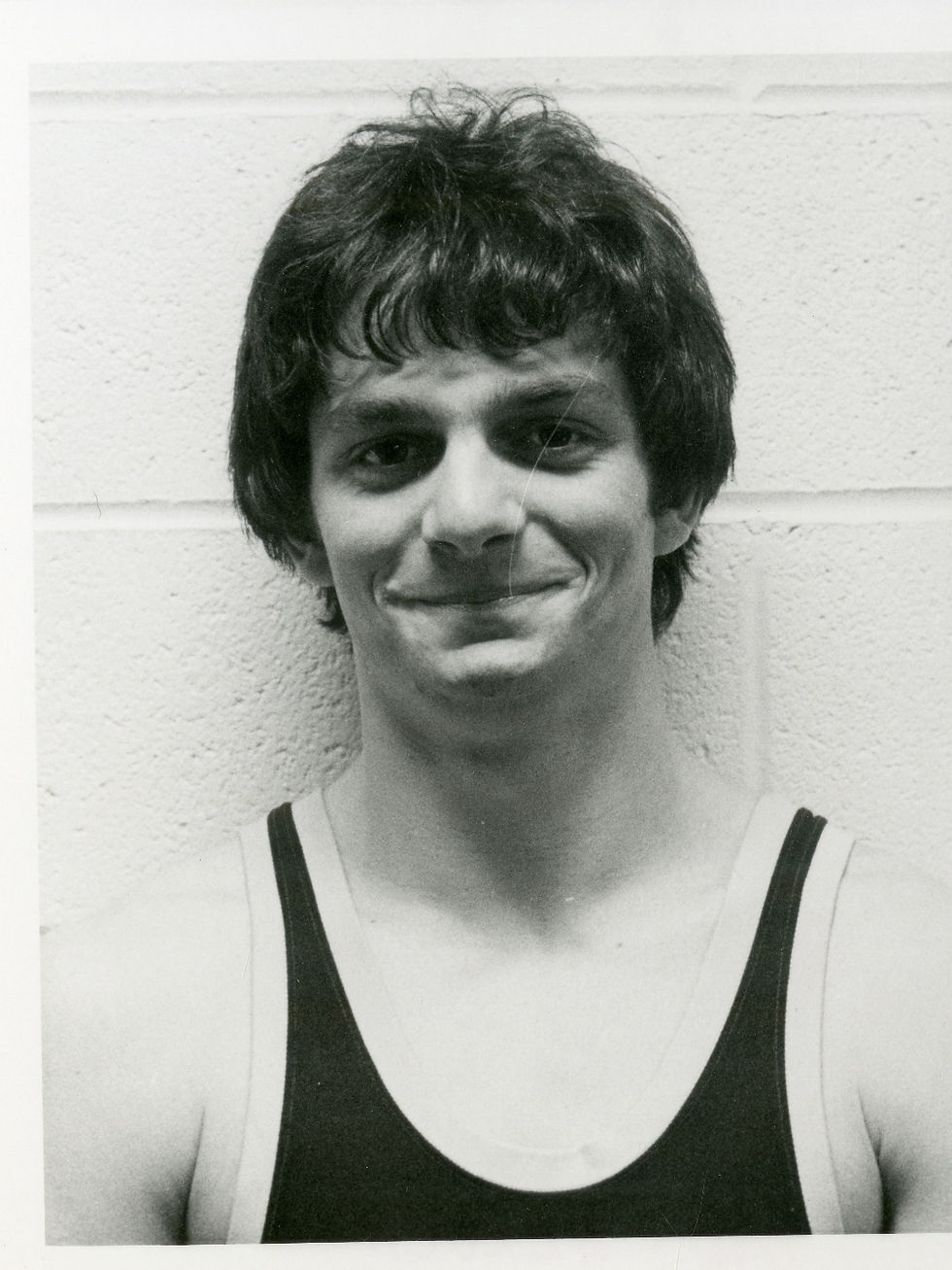

My University of Michigan wrestling story: how a good thing went horribly wrong

- Tad de Luca

- Aug 19, 2025

- 7 min read

I was 20 years old and had just finished my junior year at the University of Michigan (U-M). It had been a horrendous year. I was on the wrestling team with a full-ride that covered my out-of-state tuition and everything else. The season had started well. Then, in early November, I contracted hepatitis. I had a rash and a yellow pallor, but the team doctor (Robert E. Anderson) didn’t do a blood test, and instead, told me to keep practicing. In early January, my left elbow started dislocating in practice. I went to the team doctor, who said it was fine. After the third dislocation, I went back to him. He ordered taping for the elbow. The taping immobilized my arm and made competitive wrestling very difficult.

After a bad practice one day, I decided to go see the doctor again. I had a random conversation with a football player who told me that the team doctor was a “pervert.” The shock and grief of that statement were overwhelming. I was so embarrassed, ashamed, and upset. I was a big shot wrestler who had gone toe-to-toe with many of the top wrestlers in the country, yet I had let a man stick his finger into my rectum for his enjoyment. No, the rectal exam had absolutely nothing to do with the dislocating elbow, but just about everything to do with what happened from that point on. I vowed never to see the doctor again. My wrestling suffered.

I had seen the doctor somewhere between 12 and 20 times during my years at Michigan. In the fall of my freshman year I saw him 4–6 times at age 17 for facial herpes. Over the next two and a half years, I also saw him for a cracked rib, sore knees, hepatitis, a dislocated elbow, and even diarrhea. During each one of those visits, I had a hernia check, a prostate cancer check, and fondling that was committed under the guise of checking for testicular cancer. I had no idea that it was wrong until the football player told me so. I had no idea what a prostate even was. Forty-five years later, I became fully aware of how wrong those things were and that 17-year-old boys seldom get testicular or prostate cancer.

Not being believed: blame the victim, shame the victim

I knew that I had monumentally failed during the past wrestling season. I received several letters from the wrestling coach–Bill Johanneson–that summer. In May of 1975, he ripped into me for wasting the year. After two months, the anger inside of me was so bad that I put everything I had on paper and mailed a letter to him. I told the coach about the doctor, calling him Dr. “Drop Your Drawers” Anderson. I then went on to say, “There is something wrong with Dr. Anderson. No matter what you go in there for, you have to drop your drawers and cough.” I knew something was wrong with the doctor’s actions, but I didn’t know what it was called or how to name what it was. As an immature and ignorant 20-year-old wrestler in the 1970s, my complaint to the coach was as clear as I could be. His letter had scorched me severely, so I decided to tell him everything that happened during the wrestling season. On the very first page of my early July 1975 letter, I told the coach how I started wetting the bed during the season. I told him about my stomach aches that wouldn’t go away, and the trouble I had sleeping. I told him about the hepatitis that was diagnosed over Christmas, away from Ann Arbor. I offered to show him the paperwork for the diagnosis and the blood screening. I reminded him of the multiple and continuing elbow dislocations. Because I could barely admit to myself that I had soiled my pants on campus, I told the coach this in an unclear and a very roundabout way. I told him all of this and more. I mailed the letter.

A week later, Johanneson’s second letter of the summer arrived. I was actually looking forward to the letter because in my mind, I thought my letter to him would have cleared things up. I expected that the letter would deal with the doctor’s behavior. Nope, the coach never mentioned the doctor. The way the coach had ripped me in his May letter was nothing. He went so much further this time. He ignored many important things and mocked me. He referred to my sexual assault (rape), the stomach aches, the bed wetting, the lack of sleep, the soiled pants, the hepatitis and the dislocating elbow as “your innumerous injuries.” I remember this so vividly because I had to go look up what innumerous meant. According to Coach Johanneson, I had too many injuries to mention. According to him, it was all in my head. The coach further twisted the knife by implying that my whining about these “innumerous injuries” was “why you never were a winner at Michigan.” He then took away my full scholarship and kicked me off the team. I remember finishing the coach’s letter and being shocked beyond any ability to comprehend what had just happened. He believed nothing that I had written. He mocked me. He called me a “convicted thief” and stated that I should pay back my three years of scholarship money “much like a thief pays restitution.” I also implied and stated that there were illegal and immoral things that had happened. Coach Johanneson pondered, “why such a moral, upstanding young man such as yourself could have allowed yourself to remain in a totally immoral situation?” In this letter, he didn’t tell me that the blue sky was really green. He told me that there was no sky at all. And I believed him.

Just when I thought it couldn't get worse

It was late August of 1975. I was somewhere west of Albuquerque in my 1969 Dodge Dart and heading back to Ann Arbor. I was still in shock from the coach’s letter, I wasn’t on the team, and didn’t have any money to pay tuition. Things were bleak. There was no AC. I sat on the black vinyl seats that were slick from the heat and my sweat. All of the sudden, a thought popped into my head. It was somewhere between a revelation and a simple matter-of-fact thought. I wasn’t going to let any incompetent idiots or fools control or influence my life ever again.

Then it got worse. That September at the pre-season team meeting (I wasn’t there, because he had kicked me off the team), the coach tore into me in front of my roommates and teammates. He also read parts of my letter totally out of context. My roommates came home that night very upset. They told me some of what the coach said, but didn’t want to talk about it. I see and talk to these former roommates all of the time and they still won’t talk about it to this day.

Standing up for justice again

In January 2018, I watched on TV the trial against the Michigan State University (MSU) doctor, Larry Nassar. I saw women gymnasts whom he sexually assaulted speak in the courtroom. I immediately saw a connection between what Nassar did to them and what Anderson had done to me, and started writing a letter to the University of Michigan sometime that January. I had no idea who to send it to. I had no idea what to say. In April, I deleted everything I had written and decided not to write any more. After all, my 1975 letter had turned out so badly and I couldn’t see what I was going to accomplish with a second complaint about the doctor 45 years later.

In June, I started the letter again, but I couldn’t make the paragraphs work. I started and stopped many times. Finally, I decided to put it into an outline form and use bullet points. By July, I had a four-page outline that I was confident about. I sealed the envelope in the kitchen on July 18, 2018 and started out the door to the post office. My wife Kay said, “Are you sure you want to do this?” to which I replied, “Yes.” She then asked, “What do you expect to get out of this?” I replied, “Nothing.” Actually, I viewed “nothing” as a pretty good outcome. In my mind I imagined screaming, yelling, and embarrassment, but I had to tell U-M what had happened and clear my soul of this stain.

Was anyone going to believe me?

In late August of 2018, I had an on-campus meeting with the Michigan Title IX director. I told her my story. At the end of the meeting, she told me that she had to forward my complaint to the police. My heart skipped a beat. Even though everything I told her was absolutely true, all I could imagine was being arrested for filing a false police report. Yeah, I watched too much Law and Order.

In September of 2018, I got a phone call from U-M police detective Mark West. The interview started out difficult for both of us, but it smoothed out after a few minutes. He did a good job with a touchy subject and at the end, I felt surprisingly comfortable with him. He asked me questions. I gave him answers. I also gave him the names of five people I knew who could possibly verify my story.

I didn’t hear anything for over a year. Then, on October 3, 2019, Detective West called me. I remember this date because it was my mother’s birthday. I pulled off the road into a Lowe’s parking lot and Mark started talking. My heart was beating high in my chest and I heard the words, but was having some trouble putting any meaning to them. He said something about the five names that I had given him. Mark had called them and from those five guys, he managed to work his way to 50 others who corroborated my story. I couldn’t believe what I had just heard. Dumbfounded, I asked him, “You found others?” and “You found 50 other people who say the same thing?” I may have asked him that three times. I couldn’t believe what I had just heard.

Then, the clarity in my head happened so fast. I hadn’t made anything up. Someone finally believed me, and found another 50 people to back up my story. I was right 45 years earlier. I knew it, I knew it. Coach Johanneson was an idiot after all. The redemption was immediate and I thought it was complete. Forty-five years of guilt, not being believed, and being told that everything that happened during the 1974–1975 wrestling season hadn’t happened was stripped away during a short phone call. The sunlight was so bright. I would find out over the next three or four years that there was more redemption to come, but this initial redemption–being believed–has been the best of everything that has happened.

Tad’s story of redemption will continue in next week’s blog. Catch it as it drops on Tuesday!

Tad, you are so strong, so brave. Shame on those who chose not to believe you. “Not being believed: blame the victim, shame the victim”